L Brands: Slow And Steady Profits, But An Upside Catalyst Emerges (LB)

July 29, 2014 by admin

Filed under Lingerie Events

Overview

L Brands (NYSE:LB) is the holding company that owns the rights to several women’s apparel and accessory retailers worldwide. The company, founded in 1963 by Chairman and CEO Leslie Wexner, has, from day one, been focused exclusively on women’s apparel and accessories and, under Wexner’s vision and leadership, has grown into a company that does $11 billion in annual revenue. The stock, as seen below, has been on a very steady and strong uptrend in the past few years, with shares trading for about $57 as of this writing. Shares hit an all-time high earlier this year and in this article, we’ll discuss why I think there is more in LB shares to go higher and also why I think a strategy shift could result in even more value creation.

Brands

Before we get into the meat of the analysis, it’s instructive to understand what kind of company LB really is. The company, formerly known as Limited Brands, sells women’s accessories and apparel through retail and e-commerce channels through five brands: Victoria’s Secret, Bath Body Works, La Sensa, Henri Bendel, and PINK. These brands are focused nearly exclusively on women’s lingerie and undergarments with the exception of Henri Bendel, which sells jewelry and other accessories for women. The brands all offer shoppers an upscale shopping experience in exchange for premium prices.

Victoria’s Secret and Bath Body Works make up the lion’s share of the consolidated company’s revenue and profit and PINK brand is consolidated within the Victoria’s Secret line of business.

Metrics, Metrics Everywhere

In beginning the financial discussion, we’ll first understand where LB’s revenues come from. And as a note, all data presented are from Company Filings and compiled by the author.

As you can see, nearly all of LB’s revenues come from Victoria’s Secret and Bath Body Works. The other brands are niche boutique brands with relatively low store counts and limited product offerings. Thus, lower revenue is expected in comparison to the big two as those are well known, mainstream brands.

Hereafter, we’ll look at consolidated results, unless otherwise noted, but I wanted to form an understanding of how the consolidated results are derived from the different brands and the relative importance (and unimportance) of certain brands.

As a note, all charts show fiscal years, which have floating year end dates for L Brands depending on when weeks end near the fiscal yearend target. Thus, the charts do not show calendar years, but whatever is defined as the fiscal year for that particular year, which you can find in the company’s 10-Ks, if you’re so inclined.

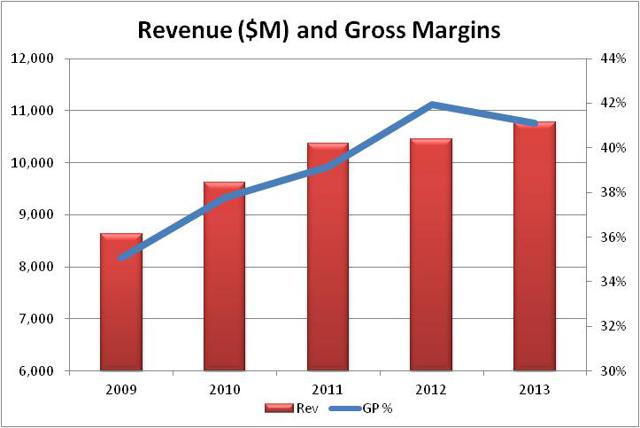

Our first performance metrics are revenues and gross margins. These are the most basic metrics of any business and for a retailer in particular, you must understand revenue and margin trends in order to gain an understanding of the business.

Here we see that both revenues and margins have increased substantially in the past five years. During the consumer-led recession in 2009, L Brands suffered mightily, seeing sales and margins trough around $8.6 billion and 35%, respectively. This was due to higher selling costs and lower efficiencies in terms of fixed costs and payroll on a smaller sales base. However, as sales have taken off and efficiencies have materialized, we’ve seen a rapid improvement in not only sales but margins as well. Prior to last year, margins had increased steadily and rapidly and while margins fell last year, the decline was very slight. The takeaway from this chart is that revenue and margins have rebounded from the recession in a big way and are showing little signs of slowing down.

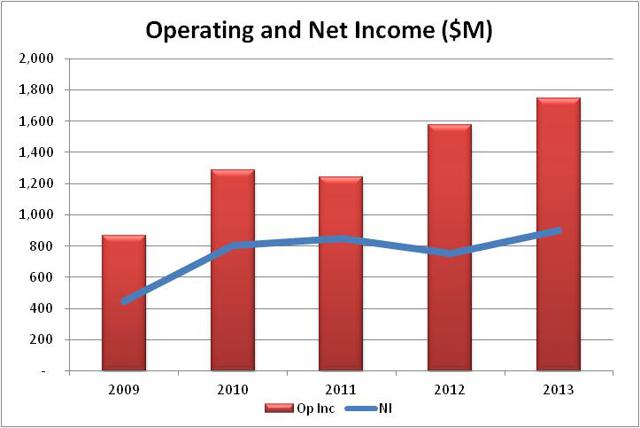

Next, we’ll take a look at operating margins and net income. We know that selling lots of product doesn’t mean anything unless you are making more money than it costs you to do so (unless you are Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) or Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)). To the rest of the world, profits matter and L Brands has that as well.

I like to look at operating profits and net income together because both are very important. Operating profit is a purer measure of profitability than net income as the latter includes all kinds of expenses that have nothing to do with actually running the business. Thus, operating income gives us a better sense of how the business is really performing without the noise of accounting gimmicks and earnings management.

Net income is also important because this is the earnings number that the Street cares about and the number by which the stock price is valued. So although I’m not a big fan of using net income because it is so malleable by talented accountants, the fact is that it matters and we must pay attention to it.

We see what we would expect to see given the first chart showing improving margins and sales; operating and net income both rose very steadily in the past five years with last year producing about $1.8 billion in operating income and around $900 million in net income. Those numbers by themselves don’t tell you much but in the context of revenue and market cap (more on that below), they can be very instructive. In addition, we can see quickly that both are headed in the right direction, showing strong and steady growth since 2009.

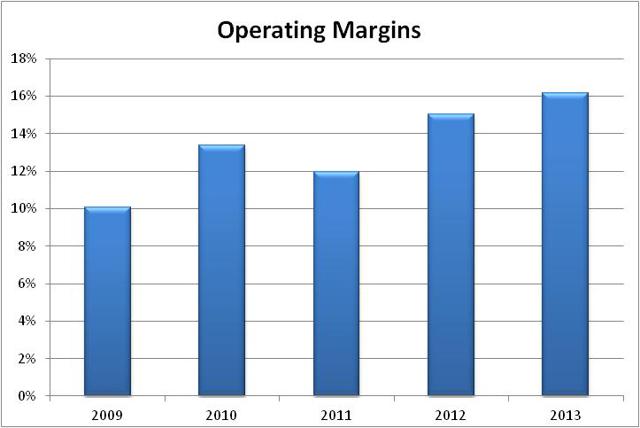

So we saw that operating profits have risen but in the context of revenue, how is L Brands doing? This chart shows L Brands’ operating margins for the same five year period.

We see that not only has L Brands been growing revenues but it is doing so while growing the amount of those revenues that flow to profit. From a base of 10% in 2009, operating margins have grown materially to over 16% last year. That is an enormous improvement in operating margins and this is a big reason why shares in the retailer have risen from under $10 in 2009 to near $60 in 2014. The company is not only growing sales but substantially increasing the amount of profit it derives from those sales. This chart is one of the most important charts you will see from any retailer and its significance cannot be overstated. LB has shown a propensity to grow profits and as long as this chart goes from the bottom left to the upper right, shareholders will continue to do well.

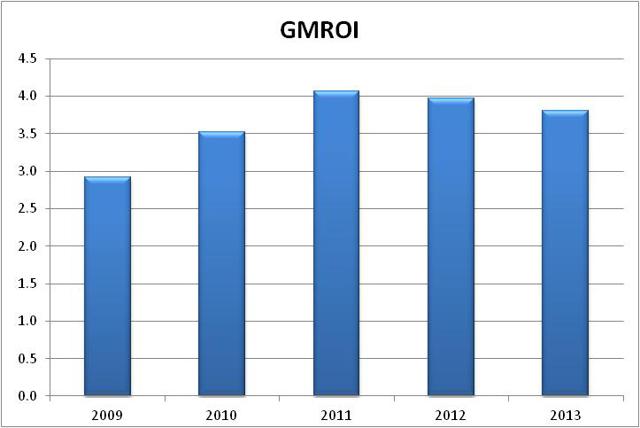

With any retailer you want to know that management is good stewards of inventory dollars. There are myriad ways to do this but my favorite is the gross margin return on investment, or GMROI. This formula takes the amount of money that is invested in inventory and compares it to how much those dollars return in gross margins; the higher the GMROI, the better.

The way it works is that if GMROI is high it means the company has high inventory turnover and/or high gross margins. Obviously, you want both but if one or both of those numbers move up, GMROI will go up. This metric is useful because it will show you if either inventory turnover or margins are declining and can be the warning sign you need to know that either margins are at risk or management is overspending on inventory. If it is stagnant or trends higher, the company is in good shape with its inventory investments.

Finally, the scale is the company’s return for one dollar of inventory investment. Thus, a reading of 3 means that the company returned three dollars of gross margin during the year for one dollar of inventory investment. This return is achieved through turning inventory over quickly and by achieving high margins.

In LB’s case we see GMROI improve very nicely from the 2009 trough until 2012 when we started to see a slight decline. Last year continued that decline and we’ve now seen GMROI come down from 4.1 to 3.7, a decline worthy of mention as it means LB is having to invest more in its inventory to achieve its growing operating and net profit numbers.

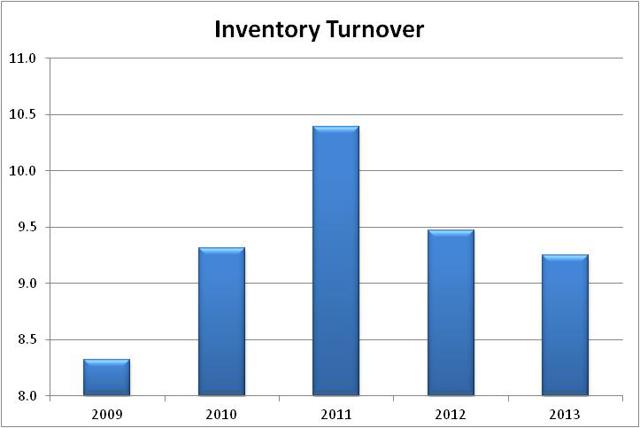

We’ve already touched on gross margins and we know that they are very near their highs for the last five years but we see GMROI has come down roughly four tenths of a point since 2011. Thus, since margins are stable and high, the culprit has to be inventory turnover.

In fact, that is exactly what we see here. LB’s inventory turnover has declined substantially from the 2011 peak and despite stable margins, we’ve seen GMROI decline as a result. If you’ve got to have GMROI decline you want it to be because of excess inventory instead of declining margins but of course, stable or rising GMROI is preferable.

LB still has very high inventory turnover so I’m not worried about it coming in at the 9+ area but if we continue to see inventory turnover slip, I’ll be concerned. LB does a remarkable job achieving $10+ billion in sales on average inventory of just over $1 billion so we are a long way from an inefficient retailer. However, as I said, we want to watch GMROI and in particular, inventory turnover, for signs that demand for the company’s products is waning or that the company is overspending on its inventory.

So why am I so worried about carrying too much inventory? The problem with that is that carrying inventory is expensive. Not only do you have to buy it but you have to store it, ship it and sell it to get rid of it and turn it back into cash that you can use to buy more inventory or other things. All of those tasks have costs associated with them and you either have to fund those costs through cash flow or debt.

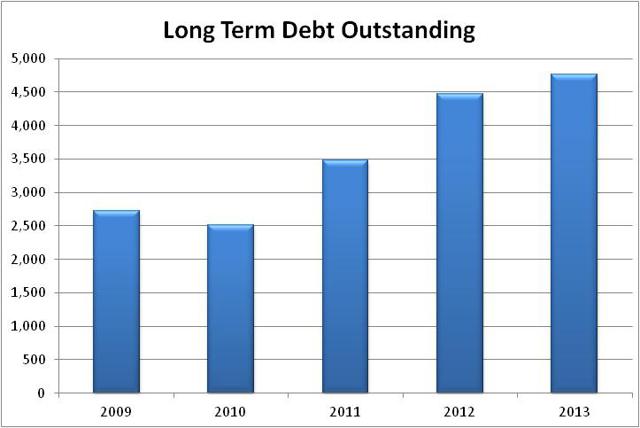

LB produces decent free cash flow, which we’ll look at later, but the inventory situation ties into our next metric, long-term debt.

LB has taken on significant long-term debt in just the past four years. In fact, the already-elevated $2.5 billion that LB had in 2010 has nearly been doubled as of earlier this year. LB’s $4.7 billion in long-term debt is very high for a company that earns less than one billion dollars per year and has FCF that is significantly lower than that. This is the one red flag that has me worried about LB; five times annual earnings in long-term debt, while not unrealistically high, is still a lot of money to owe. And the amount isn’t where the pain stops for LB either.

The weighted average interest rate on this debt is 6.8% and last year’s average daily balance of long-term debt was $4.614 billion. That equates to $300 million in cash paid for interest in 2013 and before you write off that amount, that’s for a company that earned $903 million in the same timeframe. That’s a lot of earnings being drawn away from shareholders and into creditors’ hands.

The way this ties into the inventory situation is that paying this much for debt in order to finance inventory purchases is very expensive and adds significant cost to the business model. The financing cost doesn’t show up in gross margins as there is no way to know how the money was actually spent. However, if the debt is used at least in part to buy inventory, LB’s capital structure is effectively increasing cost of goods sold, diminishing margins without it hitting the financial statements. This is where I’m concerned about LB; the company has a lot going for it but it employs a lot of leverage for a retailer.

On the plus side, LB only has $213 million in principal payments due in 2014 and $700 million in 2017; the balance is due in 2019 and beyond. This means that, while the debt is expensive to service, it isn’t going to cause a liquidity crisis any time soon for LB. I do wish, however, that the company would refinance some of this debt in the rock bottom interest rate environment we find ourselves in. Shaving even half a percent from the weighted average debt cost could save ~$25 million annually.

In addition, the company does employ some interest rate swaps as hedges against interest rate movements. The interest rate swap arrangements effectively convert the fixed interest rate on the related debt to a variable interest rate based on LIBOR plus a fixed percentage for $400 million of the shortest duration debt the company has outstanding. This is a decent start and is lowering the cost of this $400 million in debt but it is just a drop in the bucket for now.

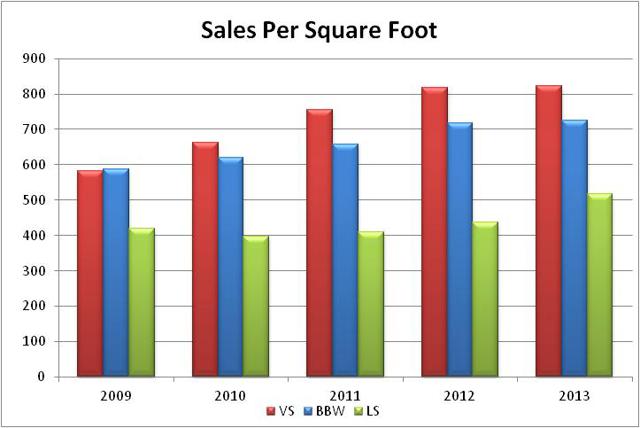

Moving back to the retail side of the discussion, LB has posted some very strong comps since the 2009 trough and we’ll take a look at sales per square foot now to illustrate just how far its top three brands have come.

All three brands listed, Victoria’s Secret, Bath Body Works and La Senza, have posted robust gains in productivity per selling square foot since the trough. We see that VS’ number has grown more quickly than BBW’s as they were virtually identical in 2009 but have subsequently risen to $824 and $725, respectively. La Senza, the laggard of the group, has seen increases but most of the gains came in 2013. Still, LS is posting just over $500 in sales per square foot when the others are well into the $700+ range. Overall this bodes extremely well for shareholders as its two largest brands are incredibly efficient at turning selling space into dollars. I’m impressed both with the direction and magnitude of LB’s chains’ sales per square foot numbers.

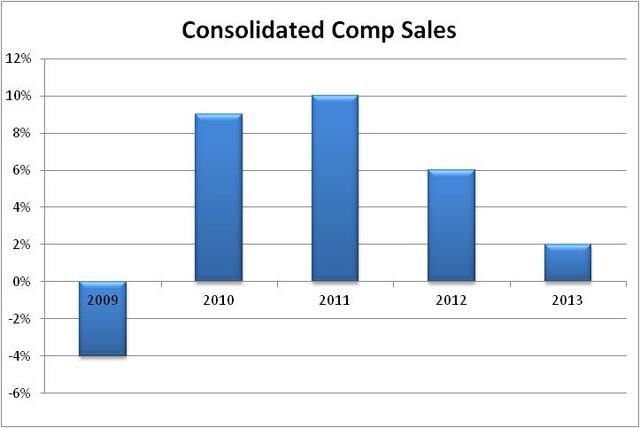

Before we finish up with some financing metrics, we’ll take a look at the company’s consolidated comp sales numbers for the past five years.

We already know that 2009 was a terrible year that saw the stock trade below $10 and, surprising to no one, the comp number was a whopping negative 4%. As ugly as that number is, the most recent four years have seen unbelievable increases in comp sales of 9%, 10%, 6% and 2%, respectively. While last year’s number was a bit of a disappointment in the context of these other numbers, it was still solidly positive and shows that, even off of a very strong base, the company delivered sales increases. This speaks to the staying power of the VS and BBW brands and the fact that the chains attract repeat customers again and again. I’d like to see the comp number higher than 2% but a positive comp on the back of a string of comp increases that we see here is quite strong indeed. I’ll be concerned if LB starts posting flat or negative comps consistently over the next few quarters but right now, I see nothing to be anxious about here. And don’t freak out if we see some soft spots in comps; every retailer has bumps in the road. It’s the trend we’re interested in.

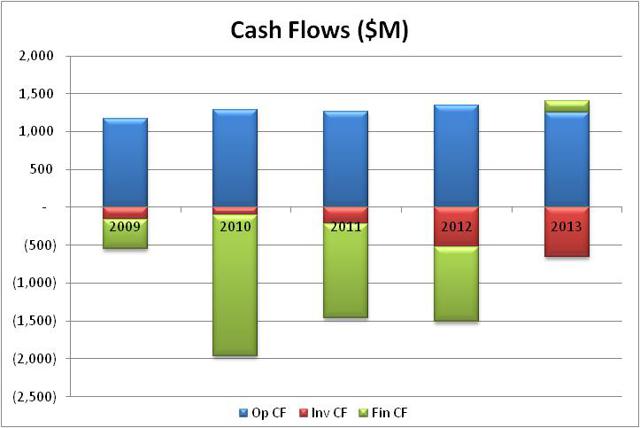

As promised, we’ll finish up the financing discussion now by looking at three more sets of data. First, we’ll take a look at the company’s cash flow statement.

As you can see, LB reliably produces $1.2 to $1.3 billion in operating cash flows each year, as seen in the red bars above. This is a strong number and speaks to the efficiency of LB’s operations. If you see a retailer that shows wildly fluctuating operating cash flow it either means the CFO and Treasurer don’t know how to manage the company’s cash receipts and disbursements or profitability is an issue. Either way, it’s a bad sign. The steadiness of LB’s operating cash flow means the company is efficient at buying and selling its inventory and converting it back into cash; I like what I see here very much.

The company’s investing cash flows, as seen by the blue bars, is negative every year. The numbers are still relatively large at $500 to $600 million for the past two years but we’d expect a retailer to show negative investing cash flows as the company is spending to grow the business. This is where we see capex show up and for a company that is opening stores every month, that number is going to be robust. We see very small negative investing cash flows in 2009 to 2011 because LB basically stopped opening new stores. However, new stores have been a priority in the past couple of years and consequently, we see investing expenditures rise substantially. Negative investing cash flows are not a big deal for a retailer so long as the numbers are small enough that the company can afford them and given LB’s operating cash flow reliability, I’m not concerned at all with its capex. In fact, I like seeing it because the company is investing in the future.

Where this gets really interesting is in the financing cash flows, as seen in the green bars. We see very large outflows every year except for last year in this dataset and the reasons are many. First, this is where any dividends and share repurchases show up in the statement of cash flows. Since LB is very active with both of these activities we see large cash outflows every year due to that (more on that later). The only reason these outflows aren’t significantly larger is because of the heavy borrowing we examined earlier. The company has posted net borrowings of $2.5 billion in just the past three years and if you were to take those inflows out of the financing section of the cash flow statement, we’d see a much, much larger negative flow than we do each year.

This is where I become a bit concerned about LB’s cash management. We already know that the company’s inventory is held in check each year and that the company is efficient at turning its inventory back into cash, so where is all of this money that is being borrowed going? The answer is dividends and to a lesser extent, share repurchases.

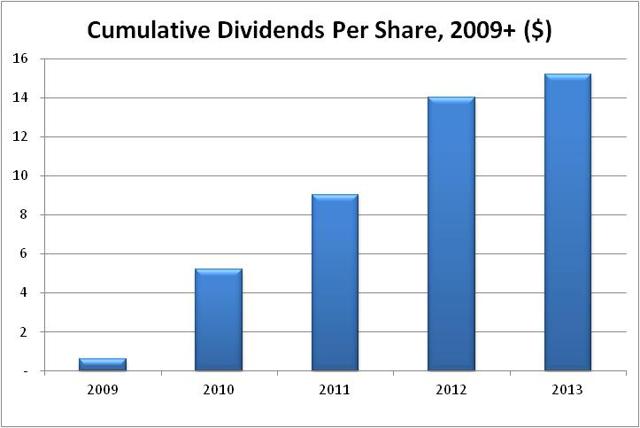

As you can see, LB has paid out prodigious dividends since 2009, aggregating to over $15 per share in that time period. On a stock that is trading for $57, that is very significant. I love this and I encourage companies to return extra cash to shareholders. However, I think LB has perhaps gone a bit overboard in borrowing money to finance dividends. Including all special and regular dividends, LB has returned $3 billion to shareholders in cash over the past three years. That is an enormous feat for a company with a market cap of $17 billion and I think it may have been too much. Shareholders are now paying $300 million per year in interest to finance those dividends and I think as a long-term decision, it may have been poorly conceived.

The other, much smaller piece of this is share repurchases.

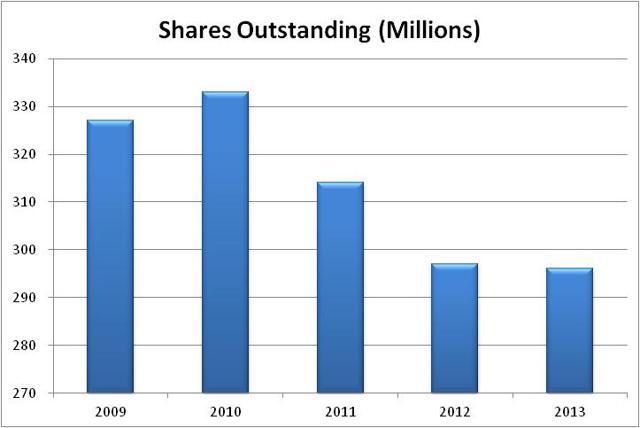

Anyone who reads my articles regularly knows that I favor buybacks over dividends and while LB has clearly chosen dividends as the preferred capital return method, it is still doing an admirable job returning cash to shareholders via reducing the share count. In the past five years, shares have been reduced from 327 million to 295 million, a reduction of around 10%. While some companies have certainly retired more shares over the same time period, I think it’s fair to say most companies likely have more shares outstanding today than in 2009 so I applaud management for shrinking the float. And since management decided to borrow money to return it to shareholders, I wish it had used the bulk to retire shares; we’d be looking at a much higher price today if it had.

This is especially true considering that management was prudent in its timing of the buybacks; most shares repurchased were bought in the $30s and $40s, meaning that significant value has accrued to shareholders as a result. Imagine what the price of shares would be today if the company had used the $3 billion it has spent on cash dividends to buy shares instead.

Valuation

This is all great but what does it mean in terms of valuing the company’s shares? We’ll begin by performing a steady state valuation of shares, assuming no strategy shift and a “business as usual” mentality. To do, this we’ll use the traditional earnings-based valuation technique.

At its current price of $57 LB is trading for 16 times forward earnings. This is a fair number that is reflective of the lower comp sales the company posted in 2013 and the early part of 2014. For a retailer that was growing as quickly as LB was a higher multiple was in order. However, recent hiccups have derailed the multiple expansion that had been so prevalent over the previous few years.

Analyst estimates have LB earning $3.16 this year and $3.58 next year, indicating strong earnings growth of more than 13%. Subsequent to that, analysts are looking for 11% earnings growth for the foreseeable future. If LB can achieve those numbers, two things will happen that will raise the price of the stock. First, the EPS base will simply get larger at a pretty rapid rate and second, that kind of earnings expansion would warrant a higher multiple than 16.

If those earnings estimates hold true LB would be earning about $4 in fiscal 2016 and a multiple range of 16 to 18 would warrant a price of $64 to $72. While not world beating upside, it’s still a nice steady uptrend not unlike what we’ve seen in the previous few years from LB; shareholders have made a lot of money from this kind of growth since 2009. And don’t forget about the cash dividends that boost returns as well.

Now, what could send that number even higher? First, LB owns an investment in a 1,300 acre planned community near its headquarters in Columbus, Ohio. The development integrates residential, recreational, office, retail and hotel space into its plans, including the Easton Town Center. On the balance sheet these investments are carried at $105 million, the cost of the investments. However, I think there could be substantial upside to this number if LB were to divest its interests or simply continue to carry them.

LB recognized a pre-tax gain of $13 million in 2012 based on the Easton investment and I believe there could be much more to come. The reason is that LB owns land and other property in Easton that, once developed, would likely be worth much more than it is carried at on the balance sheet. In addition, LB could simply lease out its owned property and collect cash on it for years to come. Of course, we have no way of knowing what the company’s plans are for its investments in Easton but we do know that upside on a $105 million investment would be material for a company that earned $903 million last year.

Consider if LB eventually divested its interests in Easton for $200 million, which would be quite feasible. While only a one-time gain that would amount to roughly 32 cents per share in gains. Or, LB could, as I said, lease out its property in Easton to produce cash receipts in the future. Shareholders should keep a keen eye trained on the company’s Easton investment as the upside could be substantial in a sale or be a source of additional cash inflows in the future. It’s also important to understand that the Easton investment is not a central tenet of the bull argument for LB; it is simply extra cash the company could come into in the future and should be considered a bonus.

In addition, I’d like to see the company divest itself of the Henri Bendel and La Senza brands as I think a spinoff or sale of those two brands could produce material upside for shares. Let’s examine why I feel this way and what it could mean for shares if it were to happen.

First, while La Senza fits the company’s brands in terms of product offerings, mirroring Victoria’s Secret in many ways, it’s very small and produces flat to negative comps on a regular basis. In addition, La Senza is more of a franchisee operation with 300+ franchise locations and only 150 company-owned stores around the world. I just think La Senza is a distraction and is taking company resources away from the profitable brands that make up ~90% of the company’s revenue. The La Senza brand doesn’t have the same recognition worldwide that Victoria’s Secret does and I think at the least, the company should rebrand its La Senza stores to Victoria’s Secret stores. In fact, the company has already written down the value of La Senza twice in just the past three years, including goodwill and intangible asset impairments totaling $325 million. The value of this brand just isn’t there and it should be separated from the two gems this company owns.

The Henri Bendel brand operates 29 stores and the chain is so small that its financials aren’t broken out specifically in the company’s filings. However, if we assume that the 5.6% of company sales that were made up of both La Senza and Henri Bendel in the first quarter were spun out or sold, we’d see a company with $630 million in annual sales given 2014′s revenue estimate of $11.2 billion. We also know that these companies are unprofitable on an operating basis, posting -$22 million in operating profit in the first quarter.

In terms of what LB could get for its LS and HB brands, that is tricky to understand. Likely the brands would be sold for some multiple of sales if the company could find a buyer. If we assume the brands will produce $600 million in sales this year and could be sold for .75 times sales, LB would stand to bring in $450 million. This is cash it could use to begin paying down its prodigious debt load and bring the company’s leverage down.

However, the real value in such a transaction would be removing the drag on earnings HB and LS are currently. Even if LB simply closed the doors on those two businesses we’d see some upside to shares. If we assume HB and LS will lose $80 million this year, which is an educated guess given that these numbers aren’t broken out for us, simply removing this drag from the remaining company would produce another $1.3 billion in market cap at 16 times earnings, or roughly 8% upside from today’s levels.

Assuming that these two brands were divested we’d see the remaining company assigned a higher earnings multiple due to increased clarity and faster growth once the drag had been removed. Thus, my 18 times earnings target from above would be too low. I think an L Brands that just contained BBW and VS would easily command 20 times earnings and thus, would see even larger upside of perhaps $80 to $90 in 2016 instead of the ~$68 I forecast from the steady state valuation. In other words, even if I’m too optimistic there is still substantial upside from closing the La Senza and Henri Bendel brands.

Wrap-Up

L Brands is a terrific company. Management has proven to be superior operators in a tough industry by carving out a niche and exploiting it to the fullest of its potential. This company is going to continue to grow into the future at moderate rates if it just continues on with business as usual but I think there is more in the business. I’d like to see a sale/closure/spin off of the two smallest brands, leaving behind a focused company that contains only the best pieces of the current business.

Kate Spade (NYSE:KATE) used to be a disjointed conglomerate of brands with the clear winner, Kate Spade, getting the lion’s share of investor attention. Management there certainly did the right thing in divesting itself of its underperforming brands and the stock has been on a tear ever since. I believe similar, if more muted, value creation could be achieved at LB if management simply rethinks keeping its two underperforming brands. You don’t, however, need to see this occur to make money with LB; it would just be a lot easier if the divestitures happened. I still like LB with or without the divestitures but the upside is so much greater with a more focused company in the model of Kate Spade.

Disclosure: The author has no positions in any stocks mentioned, but may initiate a long position in LB over the next 72 hours. The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.