Lingerie startup uses big data to make better bras

June 12, 2014 by admin

Filed under Lingerie Events

Comments Off

Michelle Lam

True and Co

When Victoria’s Secret wants to promote new products, it sends

the “angels” — that stunning band of supermodels — strutting down a

catwalk wearing glittery wings, stiletto heels, and not much

else. And Calvin Klein takes much the same tack, putting up giant

black and white billboards graced by oil-slick models lounging

moodily in all manner of suggestive poses, abs a-blazing. In the

lingerie industry, the old marketing trope is true: sex sells. But

Michelle Lam hopes that data can sell too.

Lam is the founder and CEO of TrueCo, a San Francisco-based

e-commerce startup that helps women find the right bra for their

bodies using data science. Each TrueCo customer takes a

two-minute quiz about her body before buying a bra. Then, much like

Netflix does with TV and movies, TrueCo shows each shopper

bras from a variety of brands that are a good fit for her based on

the quiz. Since the company launched in 2012, TrueCo has

collected some 7 million data points on their customers, from

details about different breast shapes to what percentage of women

experience strap slippage. Now, having successfully sold products

from other designers, the company is officially launching its own

line of lingerie that’s been specially infused with data. It’s a

move that could have implications far beyond the world of bras and

panties.

Data is the thing that allows many of the world’s biggest

companies to do what they do. It powers Google search, Facebook

ads, and Amazon recommendations. But while we’re accustomed to

online services collecting information on us and using it to tailor

their websites to our tastes, when it comes to physical goods, we

take what we can get. Sure, retailers can do market research to

predict trends, but at the end of a season, they’re invariably left

with a clearance rack full of once promising products that turned

out to be duds. TrueCo is part of a growing group of startups

that’s using data to make physical products a better fit for their

customers. “With all this virtual stuff, it’s so easy to create a

uniquely personal experience for every person,” says Lam, “but

creating physical goods that also feel like they’re made for you is

what’s incredibly fascinating to me.”

Some of the new line

True and Co

The problem Lam is trying to solve is the fact that most women

are wearing the wrong bras. The straps slip, the bands pinch, and

the cups, well, runneth over. That’s not, Lam says, because all

bras are ill-fitting. It’s because all women are different.

TrueCo’s software has found some 6,000 different body types

and counting in its customer pool. Finding the right bra could

involve hours in a dressing room, if not trips to different stores,

so most women settle not on a bra that fits well, but one that fits

well enough. Lam, who was an investor at Bain Capital Ventures

before launching TrueCo, knew this process could be improved

with technology.

TrueCo’s new line of lingerie, which includes bras,

panties, and loungewear, is based on an entirely new fitting system

for bras called TrueSpectrum. Unlike traditional bra sizes, which

only account for the size of a woman’s rib cage and the distance

between her breasts, TrueSpectrum sizes take into account whether

her breasts are full or shallow, high or low, wide-set, or a

combination of a few. The bras, themselves, have then been designed

to address the most common complaints reported in the quiz. For

instance, 62 percent of women complain about “busting out,”

particularly in their underarms. So, TrueCo designed a bra

with a high-cut spandex band to prevent that from happening.

The company launched a pilot test of four different bras last

fall, which soon became one of the company’s best selling products.

Those bras now account for more than a quarter of TrueCo’s

sales and have helped grow revenue 600 percent in just a few

months. Lam is hoping to replicate those results with this new

line. “We don’t create anything that’s not going to sell because

it’s not going to fit anyone,” says Lam. “We create less

waste.”

Novel as TrueCo’s approach may be, the company does have

competition. One startup, ThirdLove, allows women to take their

measurements at home with a body scanning technology app. And

recently, even Victoria’s Secret began offering customers a quiz on

its website. That other brands are catching on comes as no surprise

to Lam. “I look at the old retailers out there, and I see an

imperfect model,” she says. “I think this is the way women are

going to shop for intimate apparel in the future, and not only

that, but I really believe this is the way women will shop for all

apparel in the future.”

This article originally appeared on Wired.com

Share and Enjoy

Wall of Noise (Warner Archive Collection)

June 11, 2014 by admin

Filed under Lingerie Events

Comments Off

“What do you want?”

“Everything! Now!”

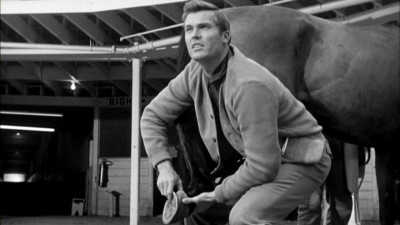

Not bad-at-all romantic melodrama, set at the famed Hollywood Park racetrack (where ironically, the horses don’t run anymore). Warner Bros.’ Archive Collection line of hard-to-find library and cult titles has released Wall of Noise, the relatively obscure 1963 drama from Warners about the grittier side of horse racing–and screwing around on the side–starring Suzanne Pleshette, Ty Hardin, Dorothy Provine, Jimmy Murphy, Ralph Meeker, Simon Oakland, and Murray Matheson. Based on a book by Daniel Michael Stein, Wall of Noise has an agreeably hard-nosed tone (at least by 1963 mainstream studio standards), while giving us a decidedly unglamorous behind-the-scenes look at the cutthroat business of horse racing. No extras for this nice black and white anamorphically enhanced widescreen transfer.

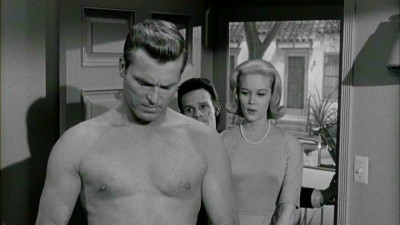

“Gypsy” horse trainer and owner Joel Tarrant (Ty Hardin) is putting everything on the line when his own horse, Frank’s Choice, is to run in a big race at Hollywood Park. Tired of moving around, working for others, while he has to make do with less-than-top colts, Tarrant sees a chance in Frank’s Choice that he may not have again: access to the “Winner’s Circle,” and subsequently breaking through to the big leagues. Helping him out are successful-but-erratic jockey Bud Kelsey (Jimmy Murphy), whom Tarrant weaned off the bottle, and Tarrant’s live-in girlfriend, Ann Conroy (Dorothy Provine), a beautiful lingerie model for whom Bud has always held a torch. Even Ann’s gruff-but-kindly boss, Johnny Papadakis (Simon Oakland), believes in Tarrant; he’s willing to lay down four yards on Frank’s Choice, just on Tarrant’s say-so. But everything goes wrong when principled Tarrant–who hates most of the owners and trainers who carelessly burn-out and destroy horses strictly to win races–excuses the horse on the day of the race, when he believes Frank’s Choice is suffering a minor-yet-potentially-ruinous leg fracture. Worse, he discovers that Ann didn’t bet their combined savings on Frank’s Choice–a betrayal of faith in his dream and his skills that all-or-nothing Tarrant can’t abide, when he subsequently kicks Ann out. Bud steps in and takes Ann to Florida–all above board, he claims–while Tarrant is pursued first by crude, crass, wealthy construction company owner Matt Rubio (Ralph Meeker), who’s hungry to buy some “class” in the “Winner’s Circle,” with Tarrant as his stable-builder, and second by Laura Rubio (Suzanne Pleshette), Matt’s wife, who’s had enough of Matt’s destructive manipulation. When Laura has Tarrant buy wild stud stallion Escadero, the emotional and sexual paybacks for all concerned begin…with a vengeance.

I’m not sure I ever heard of Wall of Noise, prior to it showing up in my screener list. Once I saw who made and it when, and who its stars were, I expected a typically glossy Warner Bros. effort from the early 60s (promising a bit more in terms of adult themes than could be found on more-popular television at the time), when Warners and the other major studios were trying to figure out how to stem the continued fall-off in returns for their once-successful formula genre pictures. Those superficially flashy titles from that time period are usually written off today by reviewers and historians as lame stop-gaps from the conservative studios who at the time still, by and large, stubbornly refused to truly let movies “mature,” if you will–a distressingly popular but dubious elitist theory, anyway, that relegates a lot of worthwhile, entertaining movies into the historical junk pile. In Warners’ case, I always suspected the studio’s deliberate use of their television contract stars in these big-screen efforts weighted many critical opinions against these outings, which only served to point out the reviewers’ snobbery towards the popular medium. Just from an economic standpoint, it only made sense for Warners to do this with their lower-budgeted movies (particularly when the box office was in such a slump at that time): just as they were the first major studio to successfully break into television production by cannibalizing their backlog of feature films, why not then make inexpensive movies with the new TV stars and contract players they created, for TV fans looking for something a little more adult and risque than they could get on the tube?

Now, had late-career Delmer Daves made Wall of Noise (which I wouldn’t have minded, either), the glitz and glamour of the location work would have been ramped up considerably (and in saturated color, no doubt), while the hearts and flowers aspect of the central romantic triangles would have been inflated (to please all the teenyboppers and housewives catching this at the drive-ins or afternoon matinees). Here, though, director Richard Wilson (1959′s Al Capone, Invitation to a Gunfighter, Three in the Attic, the Welles documentary, It’s All True) eschews the sparkly mystique we expect to encounter in such an outing, opting instead for a relatively low-key, believable, decidedly more matter-of-fact look at the goings-on at a high-stakes race track. When Wall of Noise shows us these heretofore unknown doings at the speed track, it’s fascinating like any movie that clues us into a world we’ve never seen before (not only is strategy often discussed–when to race a horse, the factors that contribute to a winner and loser–but Hardin often physically examines his animals, letting us know what’s going on with them in terms of their ability). And not surprisingly, it’s a pretty crappy world back behind the stables, where horses are merely vehicles for personal vanity and venality, as well as pawns in power games between professional rivals and scrapping romantic partners.

In producer/screenwriter Joseph Landon’s (The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, Rio Conchos, Von Ryan’s Express) script, everything–horse races and relationships–comes down to the numbers in the end. Everyone uses and gets used here in Wall of Noise, and nobody comes off clean. Provine is ostensibly set up as the “good girl” (even though we’re introduced to her sleeping naked in boyfriend Hardin’s bed), but her “right” choices are wrong in terms of her relationships: she confirms Hardin’s commitment-skittish ways by not believing in him when she doesn’t bet all their money on his last-ditch race; she plays little Bud along even though she knows he wants more; and she agrees to sleep with Oakland to pay off Hardin’s personal loan–a dubious good deed if there ever was one. Oakland’s rough and tumble modeling agency owner is set-up as a “colorful” character who seems decent deep down (although his reaction to losing a potential $80,000 on Frank’s Choice, callously saying the horse should have been burned in the race because he’s not even worth the four grand he bet, should be a tip-off to viewers). He even advances Hardin a big loan to fix a jam Meeker created; however, when Oakland finally sees his chance, almost at the end of the movie, his true colors show: he sexually blackmails Provine, crudely telling her he’s been waiting a long time to get at her (a solid, satisfying twist at the very end of the movie neatly resolves Provine’s dilemma). Meeker only seeks to enter racing to buy some “class,” just as he did when he married Pleshette, a once-wealthy society girl whose family lost their money. Described by his wife as an “animal” who really enjoys hurting people, Meeker lies to Hardin about giving the trainer complete control over his stable, undermining Hardin immediately after hiring him (“No wonder you never made it: you go no confidence!” when Hardin resists running and burning out Meeker’s tired horse). When Meeker discovers his wife’s infidelity, her prediction of his “devouring” Hardin comes true. We’re made to sympathize with Pleshette’s plight at being married to such a cruel manipulator (her affair with Hardin is made to seem liberating, particularly when they buy Escadero together, as a team). However, when push comes to shove, she’ll drop Hardin the minute he doesn’t have the cash to keep her the way she’s used to being kept by Meeker. She lays it out flat: “People use each other, especially people in love,” she warns a bewildered, scrambling Hardin; she’s not going back to poverty…even with the love of her life. And the hero of the story–Hardin, the hard-nosed idealist who doesn’t bet for fun, and who puts a horse’s well-being above all else, falls, too, when he betrays his own treasured image of himself: SPOILER ALERT! he burns Escadero for money to keep Pleshette, and for his own vanity at the chance of becoming a “winner”–neither of which, appropriately enough, come to fruition. Even though Wall of Noise has an outwardly “happy ending” final image, it’s clear the crying Hardin is completely broken over the betrayal of his own ethics.

I wish the director, Richard Wilson (apparently an acolyte of Orson Welles, no less), had been a little more adept with the promising material here; his mise-en-scene is pretty much devoid of any meaning, and his TV-like reliance on close-ups ruins crude but at least potentially interesting exchanges, such at Hardin’s and Pleshette’s first meeting, where suggestive notions of “breeding” versus “performance” are bandied about…to no appreciable effect (perhaps it was the result of budgetary constraints; few cinematographers could best Lucien Ballard at the time, but this has to be one of his least-impressive showings, with flat television lighting and boring frames). Still, it’s a workmanlike job that doesn’t get in the way of the story’s downbeat tone (Daves would have made that racetrack world a lot richer, a lot more showily “dramatic,” and a lot more vicariously sensuous…which would have seriously undercut the story). As for those “TV actors” and other B-level stars–they’re just fine here. Ralph Meeker, always best when playing a sleaze, is memorably repulsive as a vicious bully (“Whip him! Whip him! Whip him!” he yells at his own failing horse) who greasily grins, “Turning a pig into a gentleman is supposed to be your job,” to a clearly disgusted Pleshette. Provine, critically, is missing for a big middle section of the movie (a mistake in story construction that robs some dramatic tension from the movie’s final act), but when she’s on, she’s quirkily successful (and a lu-lu in slutty lingerie). Pleshette, criminally underrated at this point in her career (before she was enshrined in TV history with her sexy-but-safe “good wife” role in The Bob Newhart Show), turns out her usual smoky, smoldering, sexually frustrated housewife role with skill, while the biggest surprise here turns out to be Ty Hardin. I haven’t seen enough of Hardin to be able to claim what kind of actor he was, but here, in limited ways, he’s used quite effectively, with a square-jawed, steely-eyed single-mindedness in his pursuit of the “Winner’s Circle” that works within Wall of Noise‘s aesthetic framework. You buy his trajectory from principled-but-ruthless two-bit trainer, to “kept” society trainer and lover, to broken, remorseful sell-out. It’s not a “great” performance…but it’s a good one, in a better-than-expected meller.

The Video:

The anamorphically-enhanced, 1.78:1 framing looks a little tight at times, but it’s hard to say if this is post (wouldn’t it have been projected at 1.85?), or just the way it was shot (it almost looks as if it was prepared specifically to be shown on TV at some point–not all that uncommon then…or now). Otherwise, the image is sharp, with decent blacks and moderate grain.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono audio track is fine, with little hiss. No subtitles or closed-captions.

The Extras:

No extras for Wall of Noise.

Final Thoughts:

Straightforward, unpretentious horse track melodrama. Wall of Noise gives us a look at the race track that most of us probably haven’t seen before, while presenting a downbeat worldview that says everyone but everyone uses and gets used. Amen to that. A nice surprise, with solid performances. I’m recommending Wall of Noise.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.