Advertisement

Supported by Nov. 12, 2017

Liz Smith, the longtime queen of New York’s tabloid gossip columns, who for more than three decades chronicled little triumphs and trespasses in the soap-opera lives of the rich, the famous and the merely beautiful, died on Sunday at her home in Manhattan. She was 94.

Her friend and literary agent, Joni Evans, confirmed her death.

From hardscrabble nights writing snippets for a Hearst newspaper in the 1950s to golden afternoons at Le Cirque with Sinatra or Hepburn and tête-à-tête dinners with Madonna to gather material for columns that ran six days a week, Ms. Smith captivated millions with her tattletale chitchat and, over time, ascended to fame and wealth that rivaled those of the celebrities she covered.

A self-effacing, good-natured, vivacious Texan who professed to be awed by celebrities, Ms. Smith was the antithesis of the brutal columnist J. J. Hunsecker in Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman’s screenplay for “Sweet Smell of Success,” which portrayed sinister power games in a seamy world of press agents and nightclubs.

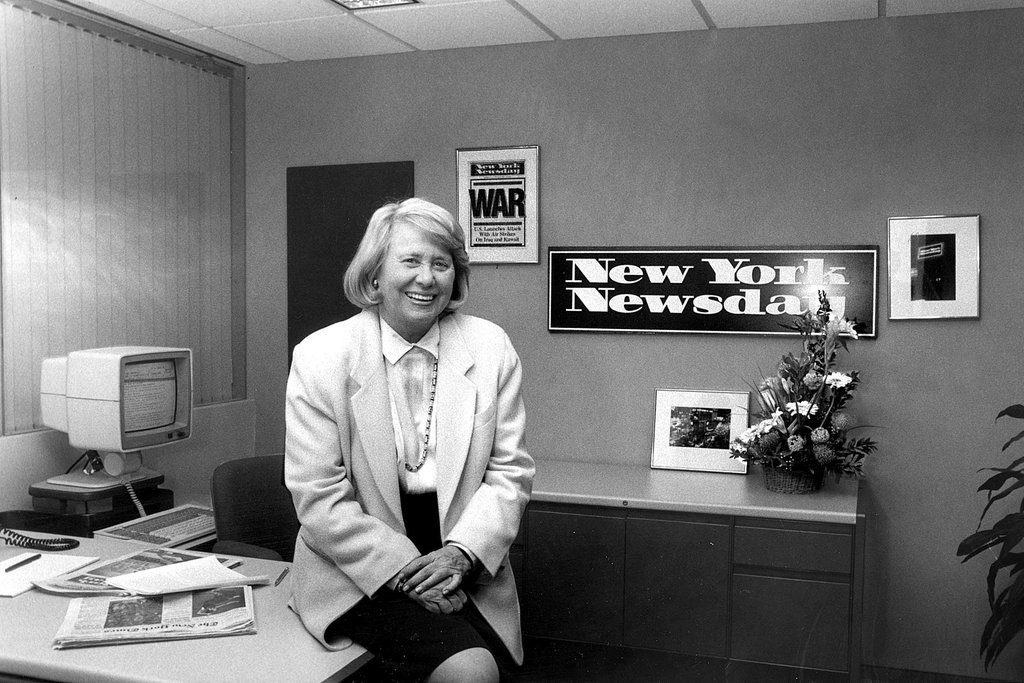

Her column, called simply “Liz Smith,” ran in The Daily News from 1976 to 1991; in New York Newsday from 1991 to 1995, when that newspaper closed; continued in Newsday until 2005; and, with some overlap, in The New York Post from 1995 to 2009 — a 33-year run that morphed onto the internet in the New York Social Diary. It was syndicated for years in 60 to 70 other newspapers, even as she appeared on television news and entertainment programs and wrote magazine articles and books.

She was not an exceptional writer or reporter, although there were occasional scoops — the 1990 split of Donald and Ivana Trump, Madonna’s 1996 pregnancy — but her income often exceeded $1 million a year, more than any newspaper columnist or executive editor, and she became as prominent as her legendary predecessors, Walter Winchell in New York and Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons in Hollywood.

Her style was not the intimidating jugular attack of columnists who expose intimacies or misdeeds in the private lives of public figures, thriving on Schadenfreude and sometimes damaging reputations. Nor, for the sake of a titillating item, did she seize upon ugly rumors or tasteless embarrassments.

On the contrary, she offered a kinder, gentler view of movie stars and moguls, politicians and society figures. And gossip was hardly the only ingredient of her columns, which were sprinkled with notes on books or films, bits of political commentary and opinions about actors, authors and other notables.

She often inserted herself into stories. Explaining why Madonna had become a regular in her columns, Ms. Smith wrote in 2006, “I didn’t always agree with what she said, or what she did, but the hysterical overreaction to her caused me, if not to defend her, then at least to put a more balanced perspective on her astonishing ongoing saga.”

If her columns lacked edge, they provided something more: the insider’s view. Many of those she wrote about became personal friends, people she genuinely liked and who liked her. She lunched with them, partied with them, vacationed with them and shared their successes and travails. And they trusted her, knowing she would not trash them in print.

But journalism’s watchdogs accused her, with some justification, of conflicts of interest, of lacking objectivity and distance from those she wrote about. The Village Voice, Spy magazine and other publications made her the butt of satires, portraying her as an egocentric, mistake-prone partisan, using columns to promote her friends.

“It’s a valid criticism, I suppose,” Ms. Smith said in a 1991 interview with The New York Times. “But I don’t know what to do about it. I don’t have to be pure, and I’m not. I mean, I am not a reporter operating on life-and-death matters, state secrets, the rise and fall of governments, and I don’t believe you can do this kind of job without access.”

Mary Elizabeth Smith was born in Fort Worth on Feb. 2, 1923, the daughter of Sloan and Sarah McCall Smith. Her father was a cotton broker whose gambling problems and fading income during the Great Depression forced the family to sell their home and move. Her parents paid bribes to keep her in her old school, but it left her a painfully shy outsider.

“I grew up with all these little rich kids,” she recalled. “I didn’t have a dime. I couldn’t face that. I was always a horrible little social climber in my way.”

Movies provided an escape. She adored Tom Mix, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire and dreamed of a career somewhere in the orbit of stars.

After high school, she attended Hardin-Simmons University, a Baptist-affiliated college in Abilene, and met George E. Beeman, whom she married and divorced.

She leaves no immediate survivors.

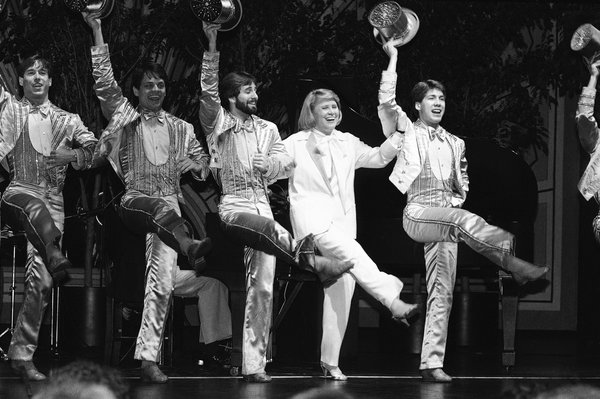

She studied journalism at the University of Texas and, after graduating, moved to New York in 1949. She took a series of jobs — at Modern Screen magazine, at Newsweek and as an assistant to Kaye Ballard, the actress and singer, who in 1953 took her on a national tour with the Broadway company of “Top Banana,” a musical comedy that starred Phil Silvers. Back in New York, she worked for Mike Wallace at CBS Radio and Dave Garroway’s “Wide Wide World” on NBC-TV.

In 1959, Igor Cassini, who wrote the Cholly Knickerbocker gossip column for The New York Journal-American, hired her to interview celebrities at nightclubs and to write the column during his vacations. In the 1960s, she was married for several years to Fred Lister, a travel agent. They had no children, and that marriage also ended in divorce.

Ms. Smith developed ideas for Allen Funt’s television show “Candid Camera”; wrote for Ladies’ Home Journal, Vogue, Sports Illustrated and other magazines; and was entertainment editor of Cosmopolitan. Besides her columns for The Daily News, Newsday and The New York Post, she worked for many years as a commentator for WNBC-TV, the local Fox channel in New York and E! Entertainment Television.

Long before her “Liz Smith” column ended in The Post in February 2009 — after being cut to three times a week in 2008 — newsprint gossip columns had been migrating to the internet and its ever-expanding blogosphere, which had become an ideal format for rapier thrusts at celebrities, often delivered anonymously and with little regard for truth or consequences.

Ms. Smith, a founder and former part owner of the website wowOwow.com, still had plenty to do, writing for news syndication, Daily Variety and Parade magazine, a Sunday supplement in hundreds of newspapers. In 2005, she published a book of reminiscences and recipes, “Dishing: Great Dish — and Dishes — From America’s Most Beloved Gossip Columnist,” a serving of celebrities garnished with favorite foods.

Her 2000 memoir, “Natural Blonde,” a best seller for months, was a breezy compendium of tales about Rock Hudson, Richard Burton, Joe DiMaggio, Sean Connery, Frank Sinatra, Katharine Hepburn and others — nothing very scandalous. Reviewers chastised her for not sharing intimate details of her relationships with women, including the archaeologist Iris Love, with whom she lived for many years.

But her work was praised. “Her brand of gossip is the old-fashioned kind, not the embarrassing or repulsive stuff dug up by so many of her journalistic colleagues,” Jane and Michael Stern wrote in a review for The Times. “When she escorts us into the private lives of popular culture’s gods and monsters, it’s with a spirit of wonder, not meanness.”

Sign up for the Louder Newsletter

Please verify you’re not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

* Required field

Thank you for subscribing.

View all New York Times newsletters.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

Trending