Full Perry quote on fossil fuels/sexual assault pic.twitter.com/KH6pyApIYU

— Timothy Cama (@Timothy_Cama) November 2, 2017

Speaking at an energy policy discussion Thursday, Energy Secretary Rick Perry suggested that better lighting in the developing world — powered by fossil fuels — could deter sexual assault.

Perry was speaking about the lack of electricity in Africa, where he said people were dying from inhaling toxins produced by open fires used to heat and light homes. “But also from the standpoint of sexual assault,” he added. “When the lights are on, when you have light that shines, the righteousness, if you will, on those types of acts.”

Call it “more lights, less crime” — the notion that well-lit spaces deter criminal behavior at night. Although it’s an assumption that many of us take for granted, evidence is mounting that nighttime brightness may do little to stop crime, and in some cases may make it worse.

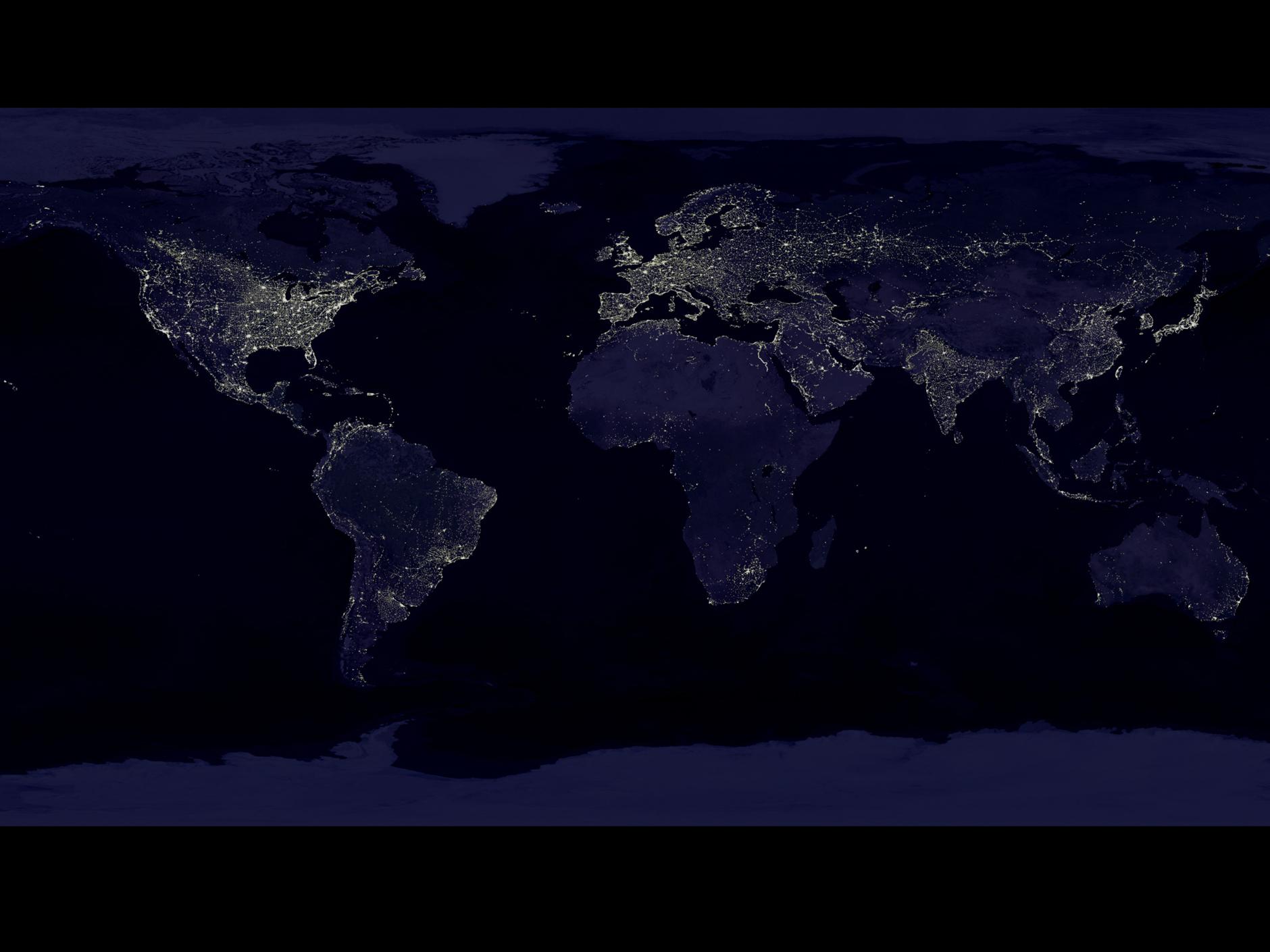

Nighttime lighting is a key indicator of economic development, and there’s no question that many sub-Saharan African countries lag behind the rest of the world in this regard. While the twinkling cities of Europe, North American and much of Asia light up those continents at night, much of Africa remains conspicuously dark in this composite satellite view from NASA — even though many of those areas are as densely populated as more developed regions.

You might assume that the link between lighting and crime is pretty clear-cut, too. In the United States, for instance, authorities in many cities prescribe light as a crime prevention measure. “Use interior and exterior lighting at all times,” the city of Sacramento warns. “Utilize outdoor lighting to make your home visible,” says the police department in West Haven, Conn.

But as it turns out, blanket claims like these are not exactly supported by the evidence. Consider the simple fact that American crime is concentrated in cities, which stand out as the most brightly-lit spots on the map above. If the relationship between crime and lighting were as straightforward as we all think it is you’d expect to see lower rates of crime in the brightest cities. So what’s going on?

As it turns out, criminologists have been examining this question for decades. Here’s what their research says:

- A 2008 review of 13 published studies on street lighting and crime found mixed evidence to support a connection: Studies in most American cities showed little to no effect of lighting on crime, while crime rates in British cities decreased when lighting increased.

- More recently, a 2015 study of nighttime lighting practices in England and Wales found no evidence that dimming or turning off streetlights at night affected crime rates or vehicle accidents. In fact, it turned up some weak evidence that dimming lights was related to an aggregate reduction in overall crime.

- A 1997 National Institute of Justice report to Congress concluded that “we can have very little confidence that improved lighting prevents crime, particularly since we do not know if offenders use lighting to their advantage.” Yes, you heard that right: Increased lighting may be beneficial to would-be criminals, in that it may help them see what they’re doing.

- A 2000 evaluation of a Chicago project to “boost lighting levels in alleys across the city as a tool for public safety and fighting crime” found that, in fact, criminal offenses increased in more well-lit areas, relative to controls.

- A 1991 study of lighting in London in the 1980s found that “on a broad scale, better street lighting has had little or no effect on crime.”

Although the research tends to not support a link between improved lighting and crime reduction, one thing is certain: People think that brighter lights at night make them safer. A 2015 study found that people in England associated “well-lit streets with competent and trustworthy government,” and that efforts to reduce nighttime lighting “tapped into deep-seated anxieties about darkness, modernity ‘going backwards’ and local governance.”

Going back to Perry’s remarks, the notion that light deters crime is probably the least baffling part of the line he drew from fossil fuel burning to sexual assault prevention. But there’s little indication that the “righteousness” of nighttime lighting will do much to stop crime in general — to say nothing of sexual assault in particular.