Catalonia Independence Fight Produces Some Odd Bedfellows

October 10, 2017 by admin

Filed under Choosing Lingerie

The decision was complicated further on Monday by a stark warning from a spokesman for the governing party of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy of Spain that Carles Puigdemont, the leader of Catalonia, could be charged with insurrection if he declared independence. The spokesman, Pablo Casado, even drew an analogy with the fate of Lluís Companys, a Catalan leader who was imprisoned for proclaiming a Catalan state in 1934, shortly before Spain’s civil war.

The separatists must now decide whether to declare independence despite the resistance of Madrid and of leading politicians in the European Union. Chancellor Angela Merkel underscored Germany’s support for a united Spain in a weekend phone conversation with Mr. Rajoy.

The foundations of the independence movement have been shaky from the start. To achieve a pro-independence majority in the Catalan Parliament in 2015, the largest political group at the time – the conservative and recently renamed Catalan European Democratic Party – ran on a joint election platform with its main left-wing rival, as well as with a minor Christian democratic party and a small group of social democrats.

This odd union was supported by some prominent Catalans like Pep Guardiola, a celebrated soccer coach, as well as the two main citizens movements that have organized mass street rallies in favor of independence since 2012.

But the separatist coalition fell short of a parliamentary majority, allowing a small and leaderless far-left party, Popular Unity Candidacy, to step in and play the role of kingmaker in a Catalan Parliament dominated by separatists. The party is determined to secede swiftly, but disagrees profoundly with other separatists on how to then shape a new Catalan republic, starting with its rejection of the euro as a currency.

The alliance is facing a major test on Tuesday, when separatist lawmakers are expected to vote on a unilateral declaration of independence.

Hard-line and far-left separatists want a decisive and rapid break from Mr. Rajoy’s national government, following the highly controversial Catalan referendum on Oct. 1 that had been suspended by Spain’s constitutional court.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But Mr. Puigdemont wants to keep on board the more moderate representatives of his own party, some of whom have grown wary about recent announcements of a corporate exodus from Catalonia. Ada Colau, the left-wing mayor of Barcelona, also called on Monday on both Mr. Puigdemont and Mr. Rajoy to take a step back rather than escalate the crisis.

The situation “is perhaps a little bit curious,” said Jordi Cuixart, the head of Omnium Cultural, one of the two citizens associations that has been organizing the separatist rallies. “The pro-independence movement has all different social sensibilities – from left to right, including pro-liberal, socialist and communist.”

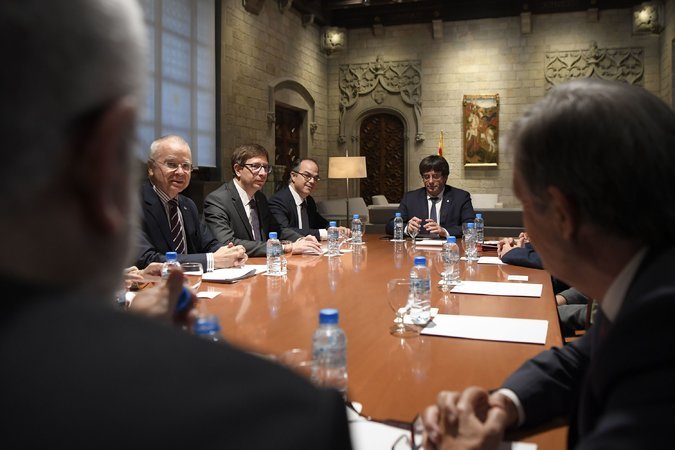

Credit

Lluis Gene/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

To further complicate the picture, the broader independence coalition includes a far-left youth movement, Arran, which hopes independence will break the neoliberal economic order that it also holds responsible for problems like the rising rental prices in Barcelona tied to tourism. Last summer, as part of antitourism protests, members of Arran slashed the tires of a tour bus and daubed it with graffiti.

Mr. Puigdemont’s Catalan European Democratic Party “is our class enemy – we are against them,” said Mar Ampurdanès, Arran’s spokeswoman. “But now we have a historic moment to break the Spanish regime, so we’re with them.”

After Spain’s return to democracy in the late 1970s, Jordi Pujol founded Convergence, a conservative party that became the flag-bearer of Catalan nationalism. During his 23 years as the Catalan president, Mr. Pujol acted as a buffer between the Madrid government and more hard-line Catalan separatists, squeezing concessions and more autonomy from Madrid without ever calling for Catalan independence.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

Mr. Puigdemont’s party is the successor to Convergence, but is a shadow of its former self, mired by corruption scandals and a tax fraud confession from Mr. Pujol himself. In fact, left-wing parties have been spearheading the independence movement since 2015, leaving Mr. Puigdemont as a captain under the permanent threat of parliamentary mutiny from the Popular Unity Candidacy.

“It has not been easy,” said Sergi Miguel, a lawmaker from Mr. Puigdemont’s party. The prospect of independence “is the only thing that keeps us together.” Some other issues, he added, are simply not discussed because lawmakers “know it would be a war.”

Mr. Puigdemont owes his job to a last-minute compromise with hard-line separatists who demanded the ouster of the previous Catalan leader, Artur Mas. Mr. Puigdemont, a former journalist, was seen as a more suitable choice in part because of his long track record of secessionism.

Since then, Mr. Puigdemont’s party has also had to accept left-wing demands over policies linked to education and support for low-income families, while winning in return support for a Catalan budget that hard-line separatists threatened to scuttle.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Quim Arrufat, a leading voice within the Popular Unity Candidacy, acknowledged that Mr. Puigdemont’s party had “agreed to things we would never have imagined.” But he still insisted that “we have compromised the most,” citing his party’s agreement not to scupper this year’s budget.

Some see the diverse nature of the independence movement as an asset, guarding it against accusations of xenophobia and extremism. “This diversity makes us stronger and makes us better,” said Benet Salellas, a Popular Unity Candidacy lawmaker.

Catalan separatism also brings together some lawmakers who are not affiliated with any of the main parties but instead represent the different migrant communities that have helped transform the Catalan population, including a mass exodus from poorer parts of Spain to Catalonia in the decades after the civil war.

“The fact that we don’t all agree on what kind of Catalan republic we want is not a weakness, but proof that we all want the new Catalonia to be much modern than Spain — and very, very democratic,” said Eduardo Reyes Pino, a lawmaker who helped launch Súmate, a pro-independence association for Spanish-speaking Catalans.

In the immensely tense current climate, as Mr. Puigdemont weighs whether and when to declare independence from Spain, the movement’s diversity has nevertheless led to differences over the best course of action, Mr. Salellas said.

Some on the right of the movement argue that “perhaps we don’t need to make any kind of declaration,” said Mr. Salellas. “And there are some people who want to make some kind of light declaration. And then there is us.”

If there is any hesitation, then Barcelona should expect further civil disobedience, said Ms. Ampurdanès of Arran, the far-left youth movement.

“Not just to pressure the Spanish government,” she said, “but to pressure the main Catalan parties to accomplish what they promised.”

Continue reading the main story